TGT #32 - Throwing a DART Successfully!; + 5 more [Oct. 1, 2022]

Everything You Want To Know About DART and the Science Behind It; The Moon Passes By 5 Planets, and Over One; Mercury Nice in the Dawn.

Cover Photo - DART, Before and After

In This Issue:

Cover Photo — DART, Before and After

Welcome to Issue 32!

Throwing a DART Successfully!

Sky Planning Calendar —

* Moon-Gazing - The Moon By, or OVER, 5 Worlds* Observing—Plan-et - From Dusk to Dawn, a Nice Bright Show

* For The Future - Planet Doings Coming Up and a Partial Solar Eclipse

* Border Crossings - No Crossings, Just Different ‘Signs’Astronomy in Everyday Life — Because We Need Some MORE Humor

The Classroom Astronomer Newsletter - Inbox Magazine Issue 36 Highlights!

Welcome to The Galactic Times Newsletter-Inbox Magazine #32 !

Nothing could top the latest This Just In, the successful smashing of a millions-dollar bare-bones probe into an asteroid, good target practice for a hopefully-never-needed-to-be-done save-the-day exercise. In the headline article, we’ll go over WHY it is necessary, with the science behind it all.

Sky-wise, as the tremendous Northern Hemisphere heat HOPEFULLY is starting to diminish (and as Hurricane Ian whooshes dangerously close to my eastern horizon, though the forecast now says nada will affect me…ha ha ha) the evening sky is a planetary paradise, with Jupiter about as bright and big as it could ever get, Saturn a jewel, and Mars making a run at Jupiter for the crown of Bright Planet Jewel of the Night. And the Moon makes stopovers by them all, and passes over one of them. Read about it in the Sky Planning Calendar.

- - -

A correction; In that article in the last TGT on the images of astronomers, the actor mentioned was William Powell, not James Powell.

Some more changes to The Galactic Times are anticipated, starting next month. Stay tuned.

- - -

Click here https://www.thegalactictimes.com for our Home Page, with all past issue Tables of Contents and stories indexed by topic. You can also hear and find useful materials for education from our former podcast on the website (plus links to other Hermograph products and periodicals).

Head here -

— for our (Free) Subscription Page and subscribe, or to read in the Archive.

If you are enjoying this twice-monthly newsletter, please support it by 1) using the link at the end to spread copies to your colleagues and friends and urge them to subscribe (why should you do all the emailing, right? We’re glad to do it!) and 2) if you are an educator, subscribe to the Classroom Astronomer Inbox Magazine, too!

- - -

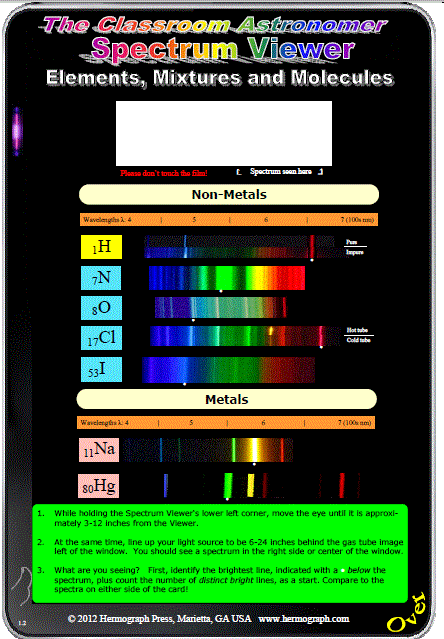

School is now in session. Educators, a hot topic is atomic and stellar spectroscopy. Do you want an easier way to see gas tube spectra that don’t involve those plastic triangular spectroscopes, with the film that gets out of place, with scales that should be by sine-theta instead of theta, and you look at both the target and the spectrum in the same direction instead of aiming one direction but looking for the spectrum in another? Then you should purchase a set of Hermograph The Classroom Astronomer’s Spectrum Viewers for Elements, Mixtures and Molecules! With 15 gas tube spectra, photographed through the same film, and printed on both sides, with a large viewing window.

For more information and purchase links, go to https://www.hermograph.com/spectrumviewers.

Thanks!

Publisher — Dr. Larry Krumenaker Email: newsletter@thegalactictimes.com

Throwing A DART Successfully!

On Monday September 26, 2022 NASA successfully crashed a small spacecraft named DART into the moon of an asteroid. It isn’t the first time NASA has crashed a vehicle deliberately into another body, but it was the first time NASA did so with the intention of crashing the vehicle, as opposed to crashing it after its work was done. In this case, the idea was to test out whether this size probe, crashing into the tiny world, could shift its orbit. Why?

Among NASA’s Missions (with a capital M) is planetary defense, something not one of its original designs. But it has become something to be considered necessary, to prevent extinctions by cosmic collisions (we’ll handle our own extinction, thank you). There aren’t many craters on Earth [Editor’s note—we’ll have a story on visiting one in a near-future TGT] but that’s because Earth’s changeable surface and atmospheric erosion has erased virtually all evidence of them. Look elsewhere; nearly every solid object orbiting the Sun shows numerous craters caused by collisions with asteroids and meteoroids. Though there are still those with conflicting hypotheses, and some recent alternative candidates added to the mix, one of the major episodes of extinctions in the fossil record was caused by a large meteoroid or small asteroid about 60-odd million years ago, crashing into the Yucatan Peninsula forming the Chicxulub Crater.

However, virtually nobody expects to see anything as large as a common asteroid hit the Earth. They are all accounted for. It is the small fry that are in the order of 10s to 100s of meters/feet that are hard to spot that are of a concern. Finding them far out is almost impossible even though there are telescopes dedicated just for that task. And if one is found that is headed on a beeline to our planet, we would have usually just a matter of days to weeks to do something about it. What can we do? The two options are destroy it, or change its path. The first is no option at all. All destruction does it turn one big rock into a bombardment of multiple small rocks hitting us in a larger rain pattern. So Plan B is to make the offending planetoid miss us completely.

To do that, you have to push it. Like anything in motion towards you, you or it have to make the shift ASAP. The earlier the better, and the smaller the initial shift can be because you have time for the small initial shift to grow over time and cause you and it to miss each other. The later you start, the bigger the shift has to be and, with rocks even a few hundred meters across, that takes a lot of energy to push it even a little bit, in order to miss OUR big rock called Earth. We just don’t have the Star Trek-like power to move big rocks at all, let alone at the last minute.

So DART — Double Asteroid Redirection Test — was sent to one of the fairly rare double asteroids, Didymos and, specifically to its 160-meter/525-foot-wide moon Dimorphos, with DART, armed with just a camera, a set of solar power cells, a navigational computer, and a CubeSat that was launched away a week before collision to photograph the smashup closeup. DART is about 50% bigger than a bus, 19 meters. The asteroids were about a tenth of an Astronomical Unit beyond Earth orbit, ~11 million miles more beyond from the Sun from us, about where we might first see an oncoming collider. It took DART around 10 months to get that far. This was no last minute flight.

By all accounts the mission was a success—in terms of its goal of making a collision. DART took photos up to collision, the last image a partial ground shot followed by static. The CubeSat from Italian scientists caught the explosion, too.

At least two Earth-based telescopes (See Cover Photo above), one NASA professional scope and one amateur level (from the Las Cumbres Observatory collection), also caught the explosion brightening and debris spray.

But did it accomplish its goal of shifting the asteroidal moon? That we won’t know for at least six months. Why?

Orbital calculations are no easy task. All objects orbit around — something — in ellipses, following Kepler’s three laws of planetary motion.

Asteroids orbit the Sun this way. But ellipses are always changing, especially for small objects like asteroids, because of the gravitational effects of multiple larger objects. The closer asteroids approach planets and (real) moons, the more the ellipses get shifted into new orientations or shapes. Furthermore, we are observing them from a moving Earth, also on an elliptical path, and what we see is a dot on an essentially 2D background. We don’t see the depth of distance when we look out at the sky.

So if you say Didymos is in an elliptical orbit that has so big a semi-major axis (half of the long dimension of the ellipse) of a certain eccentricity (deviation from a circle) orientated in a certain direction and at a certain inclination compared to Earth’s orbit, you then expect Didymos to move at a certain speed and be a certain place in the sky according to Kepler, Newton, and the location that the Earth is at. And we expect Dimorphos to be moving in its ellipse around Didymos to be predictable in its location too. But now, having given it a tiny shove, hopefully about several minutes change to its 11.9-hour orbital period, we want to see how much this Earth-collider-sized’s orbital position will shift, and that needs to take enough time for the tiny shift to add up to a bigger shift, to see if in six months it would be enough for said collider to move far enough miles to simulate an Earth-miss. We’ll also see if that makes any effect on Didymos, showing up as a positional change against the sky for it, too.

Sky Planning Calendar

Other than for Venus, October is pretty much the start of the best evening viewing period of the year! Venus will join the show better in January 2023. Meanwhile, here is what is available for the first half of October!

Moon-Gazing

Moon passages by a star, planet or deep sky object are a good way to find a planet or other object if you’ve never located it before.

October 2 First Quarter Moon.

October 4 Perigee.

October 5 Look early in the evening to see Saturn just 4-degrees north of the Moon. The Moon moves farther away as the evening gets later.

October 7 Faint Neptune is three degrees north of the Moon.

October 8 This evening, in fact closer to middle of the night, Jupiter is close, only 2-degrees, or four moon-diameters, to the Moon.

October 9 Full Moon.

October 11 Early in the evening local time on the US West Coast and Canadian Rockies provinces, the planet Uranus emerges from behind the Moon in one of the better chances to see such an event, appearing from the bare sliver of a dark edge of the just-past Full Moon. Telescope required. Just before 10 PM California time, 9 in Winnipeg, as examples.

October 13 The Moon cruises close by the Pleiades star cluster.

October 14 ….and a half. Around middle of the night, during Mars-rise, see Mars about 4-degrees to the lower right of the Moon.

Observing---Plan-et

As noted in the last TGT, on September 30 (and, effectively, our issue date of October 1st) Mars to Neptune are found in consecutive zodiac constellations, from Taurus to Capricornus (East to West), a spread along the ecliptic of 121 degrees, a third of the way around the whole sky. Some you can find as soon as the sky gets dark after sunset, the rest you have to wait for a few hours.

Repeating for emphasis, the four legitimately naked eye outer worlds (all but Neptune) are all about equally spaced apart, averaging about 40 degrees! And all of the five worlds (and certainly the three bright ones) are no farther than a degree and a half from the ecliptic so you can ‘connect the dots’ and outline the Sun’s path in the sky for a third of the year—most of the winter and spring months—and which marks the reflection of the Earth’s orbital motion around the Sun.

The planets, minus Venus, are set up for a great autumnal show! Let’s take them in planetary order.

Mercury becomes visible at least 45 minutes or more before sunrise all during these two weeks. On the 4th, you can see it, and Jupiter, both at 4-degrees above opposite horizons, the biggest and the smallest of planets! This morning apparition is the best of the the year, even if at 18-degrees it isn’t as far away from the solar glare as it could actually get. On the 8th it reaches that maximum but it rises when twilight starts and it does so, in that near darkness, for about 3 days. It is as bright as a middling ‘first-magnitude’ star, at 0.5, so it should be fairly easy to spot.

Venus is in a time-out, and won’t start to even make a glimpsing appearance until around Christmas.

Mars rises around 10 PM Daylight Saving Time but will be unmistakable, a red star of magnitude -0.6, reaching -1.2 at month end, and still brightening. Even if you can’t be sure that that brilliant red star in the East is Mars, you can be sure by finding it near the Moon on the night of the 14th.

Jupiter reached its opposition just before September ended so it is shining in prime time, from in evening twilight to in morning twilight through the 14th. At magnitude -2.9 it far outshines everything but the Moon, which is photogenically near it the night of October 8-9. It is doing a maximal Covid-separation dance with Mercury, setting as Mercury rises, on the 12th.

Saturn, the least brightest of the major naked eye outer worlds, is still easily spotted well to Jupiter’s west, and doesn’t set until around 2 AM Daylight Time.

Uranus? See above for how to find it after the Full Moon.

For the Future

All the outer planets above are in retrograde motion, except Mars. Mars begins its motion reversal, heading to the west, with its opposition halfway through it, in December and so it will stop moving eastward at the end of October. As to the others, having all had their oppositions (except Uranus, which has its in a month), they are about to one-by-one END their reversals, in the same order they started, with Saturn going first, on the 24th.

Of more key interest—to some—is on the next day…the 25th, when there will be a partial Solar Eclipse. For TGT’s readers in North America, you’ll have to take a flight or boat to the east shores of Greenland or a plane to Iceland. [Yes, Iceland is a European nation but it straddles Europe and North American continents on the Mid-Atlantic ridge.] It will be a morning or mid-day eclipse there. Otherwise it is visible as an up-to-86% maximum coverage partial in Europe—mostly northern and eastern fringes, and as far east as a line from Bangladesh northwards into Russia. A partial eclipse is also visible in Africa from Libya to roughly the Horn of Africa.

Border Crossings

The Sun is in Virgo from September 16th, and as the largest zodiac constellation the Sun will stay there for 45 days, certainly through these two weeks. Despite that, the astrologers say you should be looking to Libra the Scales. Go figger….

Astronomy in Everyday Life

I read recently that some scientists think they discovered that the meteor that created the Chicxulub crater at the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico, that purportedly killed the dinosaurs, had a companion crater elsewhere that helped the cause. Then this showed up in my feed…….

And this too, which seemed astronomically appropriate (mostly)…..

The Classroom Astronomer Newsletter - Inbox Magazine Issue 36 Highlights!

Cover Photo - Astro Visualizations

Welcome to Issue 36!

Sky Lessons -

- A Planet String in the Evening Zodiac Constellations

- 100 Hours of Astronomy October 1-4Astronomical Teachniques

- From a Smart Phone to the UniverseConnections to the Sky

- A Touch of Space Weather

- Accessible Universe

- Astro Visualizations

- Three+ Virtual RealitiesThe Galactic Times #32 Highlights

Thanks for reading The Galactic Times Newsletter! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Spread the word and get others to sign up!

You can help support this publication by:

1) also subscribing to The Classroom Astronomer,

2) ….and by purchasing other books or products from The Galactic Times’ parent company Hermograph Press. Click this link Hermograph Press’s Online Store to head to it, or

3) click the button to get to the Hermograph’s Home Page and view more details on Hermograph’s non-newsletter products!